Growing up, I spent several weeks each summer at a Girl Scout camp on an island in the Adirondack Mountains. Cell phones were forbidden (not that they would have gotten a signal anyway) and campers slept on cots in platform tents. It was an old-school place, the type your mother might describe as “rustic” as a euphemism for “slightly run-down.” There certainly was not a swimming pool beneath the floorboards of the camp’s main lodge. But back in 2007, if you read the camp’s Wikipedia entry you might have thought otherwise. “Facilities include a large dining hall, a modern shower house, a recently renovated boathouse, and a pool under the lodge,” read an edit which lasted nearly a year until someone finally removed the detail.

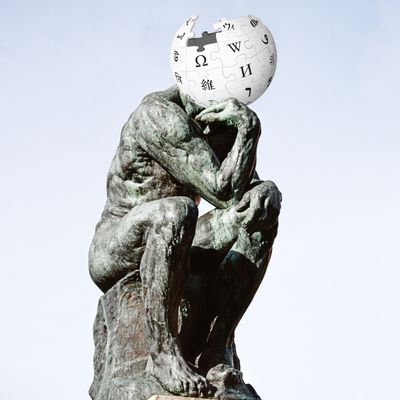

We never knew who made the edit (the user in question logged the change using their IP address) and the joke lived on in camper legend long past its deletion from Wikipedia during the summer of 2008. (It was always fun to trick new campers into believing they’d be able to reenact the Charleston dance scene from It’s a Wonderful Life in the lodge’s nonexistent swimming pool.) Entertaining as it was to myself and my then-teenage friends, the prank highlights a larger issue that Wikipedia has pushed back against since its inception in 2001. Can a crowd-sourced encyclopedia — gleaning information from faceless internet strangers — be an accurate and useful source of information?

In the early 2000s, Wikipedia as a valid source was taboo. “As educators, we are in the business of reducing the dissemination of misinformation,” the chair of the Middlebury College history department explained to Inside Higher Ed while banning student use of Wikipedia citations in 2007. Senator Ted Stevens introduced a bill that same year to block the site in schools receiving federal funding. (The bill proposed a block on all social-networking sites, not just Wikipedia.) “Just Say No to Wikipedia” signs popped up in a school computer lab in Pennsylvania. As someone who was a middle and high school student during those years, I can remember teachers talked a blue streak before any assignment about the importance of reliable secondary sources, which naturally meant no Wikipedia. It was better, we were taught, to just skip the site entirely rather than be tempted by the allure of potentially incorrect information packaged in short sentences.

There’s a reason educators everywhere, from my fifth-grade English class to Harvard, were and still are quick to warn against citing Wikipedia as a credible source of information. Seemingly any clown with a computer can edit an entry, many of which garner significantly higher web traffic than a small summer camp in upstate New York. But researchers found that only 7 percent of all Wikipedia edits are considered vandalism; that is, spam or edits designed to intentionally trick or misinform a reader. Which means the entry you’re reading after secretly Googling “Cuban Missile Crisis” under the table during a dinner party where the conversation has turned to mid-20th-century diplomacy is probably fairly accurate, if a little clunky. (While Wikipedia’s army of civilian editors might have expertise, they often sacrifice readability for accuracy, removing simplifications and generalizations that might otherwise make entries easier for a nonexpert to follow, at least compared to Encyclopedia Britannica.)

While Wikipedia hoaxes do happen (among the longest running, an article which lived for nearly 11 years detailing Sheer Perfection, an HBO show which never actually existed) most misinformation only lasts for hours or days. The site has several security measures designed to ward off vandalism, like restrictions on anonymity, requiring credible source links for information, and protecting controversial pages to ward off malicious edits. For the most part, the information you get on the site is good. A study published back in 2005 found that Wikipedia was nearly as dependable as Britannica. Something my teachers neglected to mention while declaring Wikipedia somewhere between sloth and lust on the deadly-sins scale. And unlike Britannica, where external reference links are collated at the bottom of entry pages without denoting what information came from where, Wikipedia’s numbered notes system makes it simpler to trace facts or “facts” back to their sources. A good Wikipedia article will link out to numerous other studies and news sources. If an entry doesn’t, that’s your first tip to start questioning whether or not that swimming pool actually exists. It’s like visiting the Wikipedia page for a topic does the deep Googling for you. After that, it’s up to you to parse and decide for yourself what is legit and what isn’t.

The sheer scope of Wikipedia’s info base these days makes it unignorable. It currently has over five million entries on the English site alone, which breaks down to roughly 2.8 billion words. For comparison, that’s about 60 times more words than Encyclopedia Britannica. (Worth noting that these numbers come from Wikipedia, so do with that what you will.) Looking beyond English entries, there are over 40 million articles across all Wikis in over 250 different languages. It’s no wonder when you search for anything online — French wine, the Arab Spring, Baha Men’s little-known 2015 album Ride With Me — a Wikipedia entry is usually among the first handful of search results, if not the first search result. And often the most useful.

Of course, Wikipedia has its other issues. News sites have been forecasting its death since Gawker declared the site “slowly dying” back in 2011. (Another story for another time, but it has been five years and that still hasn’t happened.) The encyclopedia has suffered from declining pageviews and interactions as more and more people digest content solely on mobile, an editorial base that has historically skewed male, an interface that isn’t terribly user-friendly for the non–tech savvy, and the possibility, as pointed out by the Washington Post in 2015, that donations which keep the site’s lights on could fall off in the not-too-distant future. Still, for now, the people’s encyclopedia lives on.

A 2014 study found that half of all doctors use Wikipedia for fast facts when treating specific conditions. Which … of course they do. Just like everybody else who Googles “weird red rash on knuckles,” Wikipedia entries are the most readily accessible. At this point, anybody who says they didn’t use Wikipedia is likely lying. Sure, you probably shouldn’t base your Ph.D. dissertation on it, but in the same way your doctor isn’t basing her entire treatment plan off a Wiki entry, the information you find there can be a great starting point. So my sincerest apologies to the fine educators who tried to teach 13-year-old me something, but “avoid Wikipedia” is the lesson I both remember and ignore most frequently. After 15 years, it’s still the sixth most popular website in the world. And we’d probably be lost without it.