In 2002, not long after I’d graduated college, gotten engaged, and moved to Japan to teach English, I got an email from my grandma. My mom, grandma claimed, did not like my fiancé. She thought he was weak. “Momma’s boy” is what she said, the email read. I just thought you should know. I’d want to.

My mom had never said a negative word about my fiancé to me. I typed a nine-page email detailing to her all the ways in which Patrick, who was still living back in the States, was wonderful. Absolutely perfect! I wrote that my mom’s inability to see his virtues likely pointed to her own personal lack. Probably, she was jealous of me — my college education, my adoring partner, my adventurousness. There was no place for pettiness and backstabbing in my life, I explained, puffing up so big it’s a surprise I still fit in my shoe-box Kawasaki apartment.

I was extra indignant about my plan to marry this man because deep down, I didn’t want to marry him. Oh, I loved him. I even liked him. But what I liked best was living in a foreign country with someone waiting for me far, far away. I was the kite that got to enjoy flying without the worry of being blown away. As long as he held my string — and he was not the type to let go — I was free. And then, suddenly, I wasn’t.

Five months in, I was still a Japan newbie. My language skills were basic; I studied every day, but my progress was slow. Culturally, I was also learning; daily tasks as simple as grocery shopping could be perilous. Because I could not read kanji characters, I once brought home a tube of vaginal cream thinking it was toothpaste (there was a picture of a smiling woman on the box).

On the day of my arrest I was in a department store, a place the others in my cohort called “Kawasaki Kmart.” I carried in my hands a scarf, a CD, and a water filter that Mr. K, the kind man at the board of education whose job was to take care of us clueless foreign teachers, had advised me to attach to my kitchen faucet.

As I browsed a clearance bin near the front of the store, the automatic doors I’d entered through ten minutes prior parted and slid open. It did not occur to me to look up. Only after a security guard had grasped my arm too tightly did I register the doors as having closed without anyone having gone in or out.

I was being pulled away from the store’s entrance, toward the back. The security guard, a middle-aged woman, spoke too quickly for me to understand her words. All I could make out were the verb endings: the harsh, command-form –tes. Kitte, aruite: come, walk. None of it made sense because none of me expected to be arrested.

As I was made to sit on a metal chair in a cramped back room, I felt fear, but also annoyance. It seemed this woman assumed I’d been planning to run out the door with my items. But I clearly hadn’t done so. Yes, I’d been near the door, but I hadn’t gone through it (which I — correctly — assumed was the legal definition of shoplifting there just as it was in the States). Foreigners were looked on with suspicion in Japan; friends and acquaintances had been stopped by police for no reason and made to show their foreign registration card; a teacher from Canada had been forced off of her bicycle while the cops checked to make sure it wasn’t stolen (bicycles get registered with the city in Japan) and while they waited to hear back from the station, asked to touch her braids and dark skin. As I waited — for what, I wasn’t sure — my annoyance turned to indignant anger. Clearing this up would take at least an hour, maybe two, and I had plans to go to the rec center and play some pickup badminton before chatting with Patrick on AIM.

But nothing was cleared up. From the store, I was driven to the police department, and eventually to a police translator’s office. At each stop, I was asked the same question in a mix of English and Japanese: Why did you steal? Have you stolen before? No matter how many times I repeated it, no one believed me. Their questions were not really questions; they were declarations of a truth different from my own.

I was handcuffed and driven to Yokohama Women’s Detention Center. The contents of my wallet and purse were inspected and catalogued. (This included my homemade Japanese flash cards, one of which contained the verb nusumu — to steal — a fact the police seemed to consider evidence of my guilt.) Nine hours passed between my supposed crime and my booking in the detention center. I had not eaten or been allowed to contact anyone, and though I was not officially charged with a crime, no one could tell me if or when I’d be released.

The place did not have standard-issue uniforms, but inmates were not allowed to wear their street clothes, either. I was handed a T-shirt that read “LET’S FUN” and tight red sweatpants that stopped mid-shin on my five-foot-ten frame. The only footwear allowed was paper slippers that ripped immediately off my size-ten feet, but because we weren’t allowed to go barefoot, I learned to shuffle without lifting my feet off the cold, polished concrete floors.

The guards debated whether I needed to remove my bellybutton ring. I heard the word renchi — they were going to break it off with a wrench — and I began to scream. The guards were embarrassed for me, which only increased my frustration and helplessness. Someone finally decided to let me keep the ring in, since cracking the metal could lead to infection. I was led, hands cuffed and with a thick rope around my waist like a leash, down a dim corridor that reeked of rose-scented disinfectant. I took deep breaths. I could see the long metal bars of cell doors ahead.

As I skated down the corridor, a ghost on a leash, I had the eerie sense that this was not happening to me, but around me. The two female guards seemed unsure as well; they bickered anxiously as to why I was there (“Yon-sen-happyaku-en?” I kept hearing incredulously, the value of the goods I’d supposedly stolen: ¥4,800, around $45.) I spread my fingers to mime a telephone call and asked, “Honcho, kudasai?” Could I please call my boss so he wouldn’t worry when I failed to show up at school the next morning? They shook their heads and averted their eyes.

We stopped in front of a cell. I was uncuffed, untied, and locked in.

My cellmates were Maria, a Filipina woman in her late 20s, and Hanako, a middle-aged Japanese woman. Maria was seven-months pregnant, and, in what now seems like a miracle, spoke English well enough to explain to me how things worked at the center. Hanako did not speak at all, though she liked to hum. Maria told me about the law that allowed Japanese citizens phone calls from prison, but not foreigners. Her people didn’t know what had become of her either.

The cell was a cement-walled room of about 8 by 12 feet, including a toilet with a low wall along one side and no door. Three one-inch-thick, plastic-covered gym mats lay side-by-side and covered most of the floor. There were no beds.

Before lights-out, Maria showed me how to sit on my knees for tenko — roll call — when the chief came through. When Chief said your number, you looked at the floor and said hai! Afterward, we were let out, one cell at a time, to retrieve our bedding from a closet. We were to grab a futon mattress and a pillow. The pillows were the size of bowling balls and filled with round plastic pellets that crunched in your ear. It was like trying to sleep on a bag of BB pellets.

I lay awake all night, tears streaming down my cheeks. I thought of something my mom had told me once, after a bully at school had punched me in the back: If someone’s messing with you, never let them see you cry. Do not give them the satisfaction.

I’d have to try harder.

The view from our cell was of a long trough where we women brushed our teeth, cleaned our faces and armpits, and hand-washed our underwear. (Upon intake, I was allowed to purchase a three-pack of cotton underwear, a toothbrush, and toothpaste with the money that had been in my wallet at the time of my arrest.) There was a clothesline strung above the sink where underwear was hung to dry. We only had six total minutes at the sink each day, three in the morning and three at night. It was hard to fit everything in.

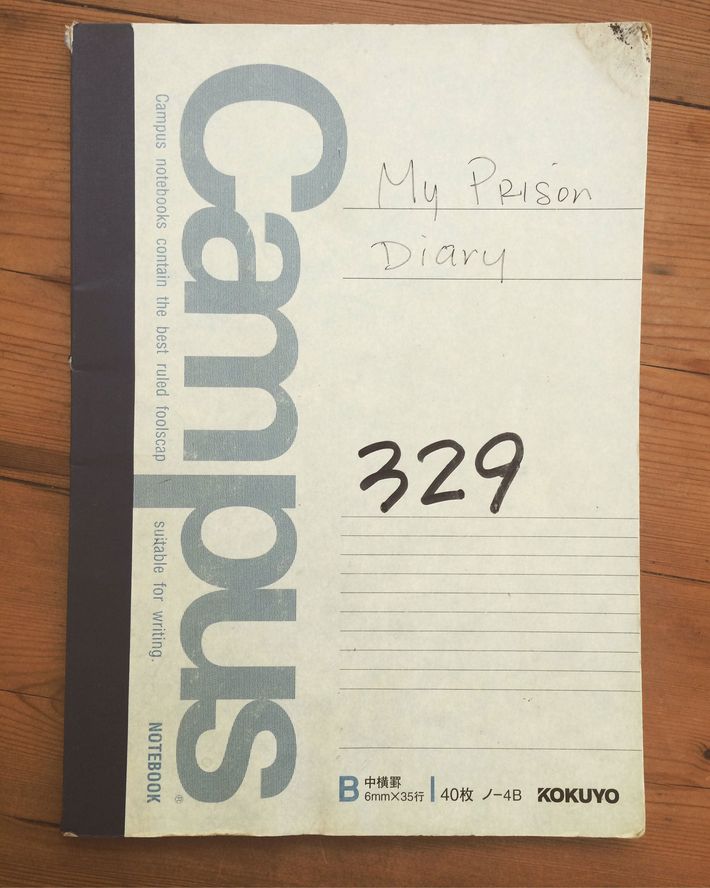

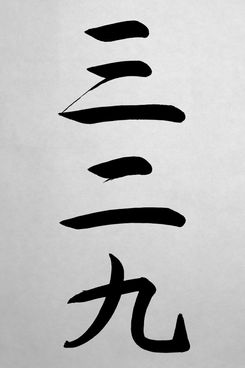

At the Yokohama Detention Center guards referred to us by our prisoner number. Mine was 329, san-ni-kyu, which when said quickly sounded like the way my beginning English students pronounced “thank you.”

I broke down crying again that first afternoon, despite my best efforts and Maria echoing my mom’s advice. I had failed to appear at school, and I pictured the teachers there, who had been so welcoming and generous, one going so far as to bicycle to my apartment on the other side of town to change my light bulb, wondering where I was, scrambling to cover the lesson I had been scheduled to teach. I thought of my email inbox and the unread messages that were surely there from my mom and Patrick.

Maria was the only person I could communicate with, and she was often asleep or in a “puss mood,” as she put it. She was uncomfortably pregnant, and sitting on a hard mat all day didn’t help.

The father of her baby, she told me, was an American marine. He was traveling now, but would be back for her and their baby once she was released. Like me, she didn’t know how long she’d be in Yokohama.

“They can keep you here a month,” she said.

“What did you get arrested for?”

“Expired visa. I worked at a club in Roppongi. The money was okay, but it’s expensive to leave the country every three months.”

I asked if she’d been in contact with her family at all, if they were worried about her. But she had no family to speak of, other than her unborn child and the marine. “He is coming to save me, wait and see,” she said.

The thought of spending a month in that place without my family or colleagues knowing where I was gutted me. I imagined my family beginning to get scared, the fear spreading to friends and more distant family. My mom, who had only flown once in her life and didn’t have a passport, might board an airplane. She and my dad might use what little money they each had to hire — who? Someone to do something. I hoped they wouldn’t.

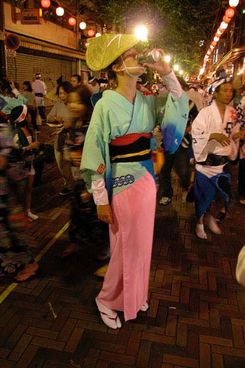

That night, after the lights went out, a voice cried into the shadows: faito, ne!

I knew this expression from the “sports day” I’d recently attended at one of my schools. It was what the kids and teachers yelled to encourage one another to try their hardest and never give up. To “fight-o.”

Maria responded with her own “fight-o,” and soon the word echoed down the block. After the guard shushed us, Maria whispered, “If you have a bad day, you can say this. Everyone will say it back to you. We fight together.”

The following morning, I was handcuffed and leashed and led to a small private room outside the cell block. There I would meet my court-appointed lawyer, an older, animated Japanese man. We communicated through my broken Japanese, written English, and charades. After five minutes of getting nowhere, he scrawled something on a piece of paper and pressed it to the glass: 4,800 ¥ only! Why jail? Strange! You are “example.”

He held it there for a minute as I read it twice, three times. If I understood him correctly, I was being held for the petty crime of shoplifting items worth less than ¥5,000, that, even had I committed it, should not have landed me here. His hand shook slightly and his fingertips fogged the reinforced glass. Did that tremble mean he was overwhelmed with sympathy? Was he as frustrated and angry as I was?

The lawyer slid the sheet from the glass. I looked to his eyes for some sign of hope, of sympathy. But he wasn’t trembling. He was shaking his head and laughing.

That afternoon, two cells at a time were allowed ten minutes in a locker-room-style shower room. I hadn’t thought to buy soap or shampoo from the guards, so I scrubbed my armpits with toothpaste.

And then the bell rang again, and again I heard the call of san-ni-kyu, and was again led to the small room. This time my visitor was a man from the American Embassy.

The consular agent’s tie had a bald eagle on it, wings spread in flight. The agent explained that, yes, it was legal to hold a suspected criminal for up to 24 days in Japan without a charge. The key, according to him, was that when I did finally see the prosecutor, under no circumstances was I to deny the charges.

Excuse me? I asked.

Things were different in Japan, he explained. If a charge is officially made and the case is sent to trial, over 99 percent of defendants are found guilty. Your situation is strange, and you shouldn’t have even been sent here to begin with, given what you’re suspected of, but …

He kept talking, but my mind was stuck on that number: 99 percent. What I needed to do, he explained, was to admit my “guilt,” show deep remorse, and sign a confession — which they would have ready for me when I came to the prosecutor’s office. If I wanted to get out before Christmas, and not miss another holiday, we had to play by Japan’s rules.

Another holiday? I asked. Today’s Thanksgiving, he said.

Life at Yokohama was about making it from one scheduled activity to the next. Mainly, this meant meals, one of the only sensory pleasures allowed. No Orange Is the New Black–style cafeteria for us: we ate in the cell. Morning, noon, and night, three trays came through a doggy-door-style opening. On each tray was separate compartments for white rice, pickles, and a thin, Peptol Bismol–pink tube of meat. At breakfast we each got a piece of fruit: banana or apple. Maria was sometimes too nauseated to eat during mealtimes, but she liked bananas, so Hanako and I always gave her ours, which she hid in the toilet tank. More than once, I woke in the middle of the night to see her sitting on the toilet, rubbing her swollen belly and peeling a banana.

My seventh day in the cell, the visitor bell rang. San-ni-kyu.

After we left the cellblock, I was led to a new hallway. A door swung open and we were outside. It had been days since I’d seen the sky. The air was damp and smelled like forest; it had just rained. I inhaled as deeply as I could. I was put in the backseat of a car. Not a police car — it seemed more like someone’s personal vehicle. We were going to see the prosecutor.

Two officers waited with me at the prosecutor’s office. They took off my handcuffs, even though they weren’t supposed to, and we made conversation as best we could. One of the officer’s brothers had gone to college in Michigan on a baseball scholarship. I told them I was from Chicago, not too far from Michigan. They shot each other with finger-guns: their imitation of Al Capone. They offered me a tangerine.

The prosecutor was stern and unsmiling, and accompanied by a Chinese woman who would act as translator.

As I sat in that office, I did not once think of Maria or Hanako, my family or friends, of dignity or pride. I had one goal: to be released. I hung my head extravagantly, I apologized for my error in judgment, I went so far as to tell the prosecutor that I was a child of divorce, which I’d been told curried sympathy in Japan. The conditions of my confession, the translator said, allowed me to stay in the country on my original visa. I would not be kicked out. I felt a spark then, though I did not recognize its meaning at the time. I signed a confession I couldn’t read.

And they let me go.

The clothes I’d been wearing and the purse I’d carried at the time of my arrest were returned to me in plastic bags; I relinquished my smelly T-shirt and the too-small sweats. My jeans were now loose. A door at the end of a long corridor led to the entrance of the detention center. Mr. K waited for me on a bench. He gave me a hug and took me out for okonomiyaki. I asked about my schools — I rotated between three — and Mr. K blew air through his lips, a sure sign that he had bad news. My schools had missed me, he said. Some kids had even sent cards. But I would not be able to go back.

“Why not?”

“You must resign,” he said.

“Resign? Why? I’m back, I can work!”

Mr. K was shaking his head. “It is difficult to say in English,” he said. The pain he felt was clear on his face.

Finally, he said: “You must resign. It is expected.”

What he struggled to translate was this: the board of education had lost face due to my incarceration; the schools knew about it — a massive embarrassment all around. And because my employer had suffered a loss of face, it was my duty to resign. It didn’t matter what the truth was. No one was interested in whether I’d shoplifted or not.

My foreign co-workers were enraged over my situation to varying degrees. A couple were even enraged at me — for not fighting harder against what was clearly unfair treatment, for not making it my life’s work to sue the Japanese government. On their faces and in their voices, I heard and read more self-righteousness than I had ever felt at any point during my ordeal. They claimed I’d been traumatized. They were mad that I wasn’t madder.

Their rage passed. Life went on. I interviewed for jobs in other parts of the country. I wanted to live someplace more rural. Someplace really out there.

Two weeks later, a letter of apology from the store security guard who had apprehended me was dropped off at the board of education. The police had reviewed the security tapes and seen that I had not left the store. The security guard had been trying to meet a quota and felt that I, as a foreigner, would make an easy target.

Mr. K read the letter in translation, while I sat listening, frozen with shock. Here was the moment I had dreamed of since my arrest, and yet I did not feel particularly happy. I had grieved the unfairness of my situation and had come to accept that I would never be vindicated. While at first I suffered, helpless, at the thought of people assuming I was a thief and criminal simply because I’d been accused, I had steeled myself against this discomfort with the Japanese phrase sho ga nai — “It can’t be helped.” I couldn’t control peoples’ opinions, and if they wanted to believe I was guilty, I couldn’t stop them. The people who loved me had supported me, and that was all that mattered. Plus, I knew the truth.

So I was not as pleased by this revelation. A clean record was helpful, but emotionally, it meant little. I could show this letter in fancy calligraphy to my family and friends back home as evidence that I wasn’t a thief, that I had been “right” all along, but suddenly that notion that had been so important to me — that people believe me and see me as right — didn’t seem to matter as much.

My exoneration did not change the fact that I needed to resign. Loss of face is a one-way occurrence. Truth cannot undo it.

My new job was in the mid-sized city of Tokushima, on Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s main four islands, where the old ways of living still held fast. My new boss, an energetic, ambitious woman, wanted a new style for her school, and she loved my ideas.

Mr. K drove me to Haneda airport, where I boarded a small plane bound for Tokushima City. He had tears in his eyes as he handed me my going-away gift: a double CD of his favorite J-folk band, Kaguyahime. He remembered that I liked to play guitar and sing and that in my self-introduction, I had said that I liked Simon and Garfunkel. After takeoff, I listened to the discs on my Walkman while staring out the window at the Pacific Ocean. I wondered if the week in the detention center had changed me at all.

Months later, when I told my mom that Patrick and I were breaking up, she did not lord it over me or say “I told you so.” She never mentioned the email I’d written to her in which I’d said hurtful things in order to prop up a self-serving fiction. She listened, empathized with me over the breakup, and asked questions about my new love, the man who, ten years later, I would marry. Version 2.0 of my life in Japan was turning out far better than the original.

I was apprehended in Japan. I was, from the Latin, “laid hold of.” I had been accused of a crime I didn’t commit, but that didn’t mean I was blameless. There were harsher crimes, crimes of the heart, I had engaged in. Agreeing to marry a man I knew I’d never marry. That prideful letter to my mom. Confessing to those heart-crimes of which I was guilty was much more difficult than confessing to the legal one of which I was innocent. There’s something essential, too, in accepting what is true over what is easy. Perhaps we need both: to face consequences and briefly forget them, moments in which we let slip a “fight-o!” Moments where, despite the bars that hold us, we are free.

Kelly Luce is the author of the story collection Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail and a fellow at Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Her debut novel, Pull Me Under, is out this month from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.