Last Thursday, President Obama commuted the sentences of 98 prisoners, 42 of whom had been in for life. It was not just a late-in-the-presidency gesture, but rather the latest in what’s been a remarkable focus on criminal-justice reparations: The announcement brings the number of commutations granted under Obama to 872, more than those of the last 11 presidents combined.

After the Department of Justice announced a clemency initiative in 2014, more than 35,000 inmates in federal penitentiaries across the country requested assistance. Sentencing activists called the initiative more symbolic than practical; by granting so many commutations, the president was acknowledging a systemic problem, not fixing it. Still, for the people who have benefited, the project is anything but abstract: It gave them their lives back. Below, four of them tell their stories.

Evans Ray Jr.

President Obama commuted Ray’s sentence on August 3, 2016. Ray was 12 years into a life sentence for distribution of cocaine and crack cocaine while in possession of a firearm.

The Crime

December 16, 2004, the FBI, DEA, and county police, at about 5:45 a.m., attempted to knock my door in. Before they could knock the door down, I opened it for them. They didn’t say anything. They ran in with their infrareds and lay everybody down. It was one of the coldest days of the year that day. My son and daughter, one was an infant and my son who was 3, they were asleep. They lay me down on the floor in the living room. They lay my wife down in the basement because she was getting her clothes ready for work, and they started just ransacking the house. They were looking for drugs, guns, whatever they could find that would tie me into a drug conspiracy. I complied. You don’t want to get shot.

They told me I was charged with conspiracy to sell cocaine, with the guys whose clothing store was next door to my barber shop. In 1990, I had been locked up for cocaine. I received a 12-year sentence. I did 88 months. In ’93, my sister was coming to see me. She was driving down to see me, and her truck turned over. She was killed instantly. I took that so hard. I met a guy then who was the barber on the compound. The barber was with me just about every day after my sister died. We became close. He was one of the main informants on the case in 2004.

He called me saying his family was in trouble, asking if I could help him out. Eventually, I did. I made two transactions. I’m not denying it. I made those transactions because he was there for me when my sister died. He was working with the agents the whole time. My defense for my trial was entrapment.

Even before I was found guilty, the prosecutor slid an envelope to me and my lawyer that said 851 with the enhancement papers. That meant that if I was found guilty of a certain count that I would receive life in prison because of the three strikes from my previous crimes. The judge fought that so hard. He told the prosecutor, “That’s a cruel and unusual punishment.” So he sentenced me to 324 months and told them if they didn’t like it to appeal it. They sent me to the supermax up near Baltimore. Five days later, they called me back and Judge Williams said his hands was tied and that he had to give me life under the law. I felt like the world had crashed down on me.

Going in and Getting Out

I ended up in the worst penitentiary in the BOP. Big Sandy; we called it Killer Mountain when I got there. So many stabbings, so many murders. It’s in Inez, Kentucky. I’ve never had any violence in my jacket. I’m a nonviolent person sent in with a bunch of lions and wolves.

My first day, we get off the bus, we get seen, we get screened, we go to our block. Me and an older guy are walking the track. Another guy from out of Washington comes over and says, “Are you the guy from Washington?” I say yes. He said, “Come over here ‘cause somebody’s about to get stabbed.” As soon as we got on the other side, the guy got stabbed in the throat. That was my first day there.

I tried so hard to get out of there, and I couldn’t. We got sentenced there in ’07, and I might have almost given them a year there. Because I had high blood pressure and cholesterol, they moved me to another penitentiary. I learned to mind my business. Stay out the way. Keep moving. It could happen to anybody at that place.

They transferred me to a place called McCreary, that’s in Pine Knot, Kentucky. In May of 2014 there was a stabbing, and so they put us on lockdown for about a month. When we came out of it, we got on the computer, and they had the Clemency Project 2014 on there. They wanted us to fill out the questionnaire. I filled it out and submitted it. About two months later, someone got in touch with me from the federal defender’s office in Upper Marlboro. They said they were giving me an attorney. The lawyer out of the federal defender’s office, when she went through everything, she said, “Mr. Ray, you have a poster-child case.” I didn’t know what that meant. I remember seeing the little kids on the milk cartons and all that, right? She said, “Look, you fit all the criteria that Obama’s asking for. You have a good shot.”

For me, a commutation wasn’t like hitting the lottery. It’s more like: I put my income-tax papers in and I’m waiting on my check. You know your check is coming, you just don’t know when. I was confident because 60 grams of crack cocaine does not warrant a life sentence.

In May of 2016, I wrote Obama and his wife a letter. Just a personal, short letter, telling Mr. Obama and Mrs. Obama that, “I’m writing you because y’all only got seven months left and I want to thank you for all of the positive things that you’ve done for the community for all races, white, black, and Hispanic.” I told him that, “You gave guys like me a sign of faith.” The middle part of July, he wrote me back, and nobody could believe it. He said to keep the hope, have faith. He never said I was going home. But the staff was like, Obama receives thousands of letters, how’d he just pick yours?

The judge in my case wrote a letter saying he felt that my sentence was cruel and unusual and that he never wanted to give me life. The judge really got the ball rolling. A lot of judges are hesitant about doing something like that for guys. He knew I was sentenced unfairly. He didn’t have to do it.

The day I found out was August the 3rd, 2016. My unit manager came and knocked on my door and said, “I need you in my office at one o’clock today.” My grandmother’s 96, she’s very old, and bed-stricken. So I said, “What’s wrong? Something going on with my grandmother?” She said, “No, there’s nothing going on with your grandmother.” I get back there and sit there with her. At 1:10 she makes a phone call and says, “What’s going on? We haven’t gotten the call yet.” I’m kind of thinking something about clemency, but I’m not sure. At 1:16 the phone rings, she answers it, she’s grinning ear-to-ear, so I’m thinking something now. I get on the phone and the guy says, “Are you Evans Ray?” I said, “Yes, sir.” And he says, “Mr. Ray, the life plus ten years, Obama has taken it away from you.” I said, “Going home?” He said, “Yeah.” I’m sitting back in the chair like, I can’t believe it. It’s unbelievable. It’s crazy. He said, “Are you still there?” I said, “Yes, sir.”

When she let me out of the office there were guys standing on the chairs like, “You got it! You got it!” And I said, “Nah, nah. What y’all talking about?,” and I walked to my cell and I put up my sign so no one could see in, and I got on my knees and prayed and I thanked God. When I got off my knees and came out, everybody — I’m well liked in there — was all over the place saying, “You got it! We know you got it!,” and I threw my two hands up in the air and said, “Yeah, I got it!” They started clapping and hugging me.

Freedom

When I got out, we went straight to my grandmother. She’s on her deathbed, and all she ever wanted was for me to come home. I didn’t tell her or anybody I was coming. I remember going up the steps — it’s the house that I was raised in — and she was lying in the bed in the den. She could move her neck and her head, but no other parts of her body move. She’s very sharp. She says, “Is that my baby?” I said, “Mama, it’s me.” And that was the first time that I shed a tear. I cried like a little baby in her arms.

I stayed with her for about an hour, but I’m on the clock, I’ve got four hours to get to the halfway house. We leave there and ride out to my mom’s house. My three daughters, my son, my nieces — everybody was there. It was just a lot of crying, a lot of hugging. You know how the kids can take your phone and draw funny faces of you? One of my daughters, she’s sitting across from me — she’s my heart — and I don’t know anything about these phones, and she’s doing something, but she keeps looking at me. So when I get the phone, what she shows me is me looking like a clown with some ears and all this. It was her way of saying, “Dad, you’re home, and I love you, man.”

The hardest thing for me is just adjusting to this social-media thing. Everybody is speeding, like a bunch of zombies with their heads down and their thumbs moving. It’s new to me. When I left, everybody was using flip phones, Nextel. Now everybody is Googling and texting, and I’m used to calling people. I call people and they won’t answer, but if I text they answer.

The other day when I was home for 13 hours, my 16-year-old son stayed there with me at my mom’s house. We were watching a movie and he paused it and he wants to order a pizza. I said, “Go ahead and order, man, I’m eating what you eating.” He ordered cheese, chicken, and pineapples. I said, “Pineapples?” He said, “Dad, you going to like it.” I’m going to be honest with you — it was the nastiest pizza I’ve ever tasted! But I ate three pieces and told him I loved it.

Jason Hernandez

Served 17 years of a life sentence for possession with intent to distribute crack cocaine.

The Crime

I was indicted for conspiracy to distribute crack cocaine. I went to trial. I got life without parole. Of course I didn’t believe it. I was a first-time drug offender — no guns, or gangs, or links to cartels. Nothing like you would picture like Scarface or New Jack City. Not that that made it right or anything, but I was thinking, Not even real drug dealers get life sentences, there’s no way I’m going to get that much time. But I did.

Going in and Getting Out

I went to a United States penitentiary. It wasn’t like nothing you would figure as far as people talking about Club Fit or Club Cupcake. The place I went to was one of the worst penitentiaries in the United States. People there got murdered and stabbed and assaulted. I was just a young kid, just going with the flow of things and doing stupid stuff. I was drinking, smoking weed, stupid stuff like that with the other inmates. Really wasn’t trying to do too much as far as trying to get out. I just accepted it.

In 2002, one night in March, all the guards were looking for me. I thought I was going back to court. It was just kind of unusual the way they were looking for me. So I called my dad, he was crying. It was the first time I’d ever heard my dad cry. He was like, “They killed him.” I had another brother. He was doing 30 years in the Texas Department of Corrections for five grams of crack cocaine. He got stabbed. I just couldn’t believe it. Even though I was at the lowest as I could be — serving life without parole — that kind of drove me insane for a little while. My brother wasn’t born to die in prison. I thought, I’m going to do everything possible to try to get out of here and change my life.

I started taking paralegal classes and working on my own case. I did everything possible, filed all my appeals. Everything got denied. Over the process, I got pretty good at it. I would do other appeals for other inmates. I made a little money as a jailhouse attorney. I did child-support cases and child-custody cases and divorces. Divorce is pretty high in there. That was my little side hustle.

Then I read a book called The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, and that inspired me, too. You know the war on drugs was basically aimed toward minorities through the Nixon administration? I started doing a survey of the prison. There were 17 people there doing life without parole; 15 were minorities. We were all drug offenders. There were two white people there that were doing life and they had committed murder.

We reached out to a lot of organizations, and nobody would talk to us, even sentencing organizations. “Life without parole for drugs? There’s something you’re not telling us about your case.” Nobody wanted to help out.

I took a picture of ten of us that were serving life without parole for crack cocaine, nonviolent offenders. (There were others, but we could only fit ten in a picture.) I wanted to get that picture and send it to Michelle Alexander. She inspired me to start a grassroots organization, Crack Open the Door. We ended up creating crackopenthedoor.com. We put the website up, put profiles up of all the inmates that were in prison, to try to humanize us, to show people that we’re just normal people. We’re mothers, we’re fathers, we’re sons, we’re daughters. I sent that picture to Michelle Alexander. She responded, “Look, I can’t help y’all, but I believe in what y’all fighting for. What I can do is connect you to the ACLU.”

I ended up doing my petition for clemency to the president. When I tell you that I put it together like my life depended on it, I did. It probably took six to nine months to do that petition. I knew there were tens of thousands of petitions filed, so when I did this petition, I said, “How can I make mine stand out?” I put a hardback cover on it. I put it in binders, I put tabs. I put a personal letter to the president, pictures of me, all the certificates and awards I got while I was in prison. Support letters from preachers, schoolteachers; I put a release plan, my goals of what I wanted to do when I got out. I had a message from the officer that put me in prison attached to it. There was no guide on how to do one. There was no class or something you could Google to find an above-average clemency petition. Everybody would laugh at me. I was always in the library doing legal work. They all laughed, saying, “Come on, man, you know we don’t get that.” They were basically saying that minorities — you know, Mexicans and blacks — don’t get clemency. It’s more for white-collar criminals.

I sent that out, and probably about two years later I’m in the prison and they’re calling for me — same thing as when they called for me when my brother died. I got real nervous. Probably my mother or father passed or my son. I got cold chills. I go to the guards, and they take me to the front of the prison and put me in the warden’s office. Next thing you know, the warden comes in and he’s like, “Your name Jason Hernandez?” I said, “Yes, sir.” And he goes, “Well, I’ve got an executive order from the president of the United States, Barack Obama, commuting your sentence of life without parole plus to 20 years.” I just started crying. It’s over. It’s over.

Freedom

They put me into a halfway house for about a year. Getting a job was hard. Nobody wanted to hire me. I had two trades: welding and paralegal work. Some people didn’t really care that I had a conviction, but I had no work history. I’d never worked. I was in prison my whole working life.

Some people would say, “I don’t care that you have a conviction; everybody’s got a conviction these days. As long as you didn’t assault anybody or a crime against a child or anything.” I’d say, “No, it was just a drug charge,” and they would ask how long I was in prison. “Nearly 18 years.” Their eyes would get real big, and they’d step back from the table. “You were in there for drugs? No, you must have done something else, you’re not being straight with us.” I’d say, “No, sir, it was a nonviolent drug charge.” They wouldn’t hire me.

I went to Whole Foods and was like, “Can I speak to a manager for a job?” They said, “Oh, you apply for a job over there.” It was a computer. I walked to the computer and was like, “Oh my god.” I just got an anxiety attack. I don’t know what to do.

After that, I was like, What can I do different? I was in a Time magazine article, so I brought that and the certificate from the president. So when it says check the box for criminal history and explain, I checked the box and just wrote, “I will explain.” The lady asked, “What does this mean?,” so I showed her the certificate from the president and my article. Next thing you know, she called her co-worker, then called another co-worker, then everybody’s in there looking at me and smiling and congratulating me. She said, “I’m going to call the manager and put in a word for you. Just come tomorrow so you can start working.”

In prison, guards are always watching you, or cameras, and I would just always get this feeling that everybody’s looking at me. They’re not. But you just feel like that.

It’s hard to go out on a date and tell a girl and try to keep your conviction away from her. I work at a drug and alcohol recovery center; I still have crackopenthedoor.com; I was working at a restaurant called Cafe Momentum, where I was a mentor for formerly incarcerated youth. So when they ask, “Why do you do that?” I can’t escape the fact that I have to tell them that I was in prison. Once you tell a girl that, they’ll tell you, “Hey, I’m happy for you, but I just don’t want that in my life right now.” When someone asks, “Where do you live?” I have to say, “Well, I live with my mom and dad. And I’m 40 years old. Just barely got my car.” “Hey, where were you at when 9/11 happened?” “Well, I was in prison.” It’s just something that I can’t avoid.

My son was 6 months old when I went in. He was 18 when I got out. It’s not like the father-and-son experience like I had with my father. I wasn’t there for his entire life, basically. Initially, he wouldn’t call me Dad, and when I would tell him I love him, he wouldn’t respond. He wouldn’t spend time with me. But about three months ago, for the first time since I got out, I said, “I love you, son” — it was on the phone — and he goes, “I love you, too, Dad.” Man, I was like, Oh my god! I didn’t say nothing. I kept all my enjoyment inside. I was trying to play it cool. I just said, “I’ll talk to you later.” But later on that night I called him again and said, “Hey, what are you doing?” Really, I just wanted to hear him say it again. So I said, “Hey, I love you,” and he did. Now he calls me Dad. He didn’t get involved in the stuff I did. He graduated. And a few months ago I did, too.

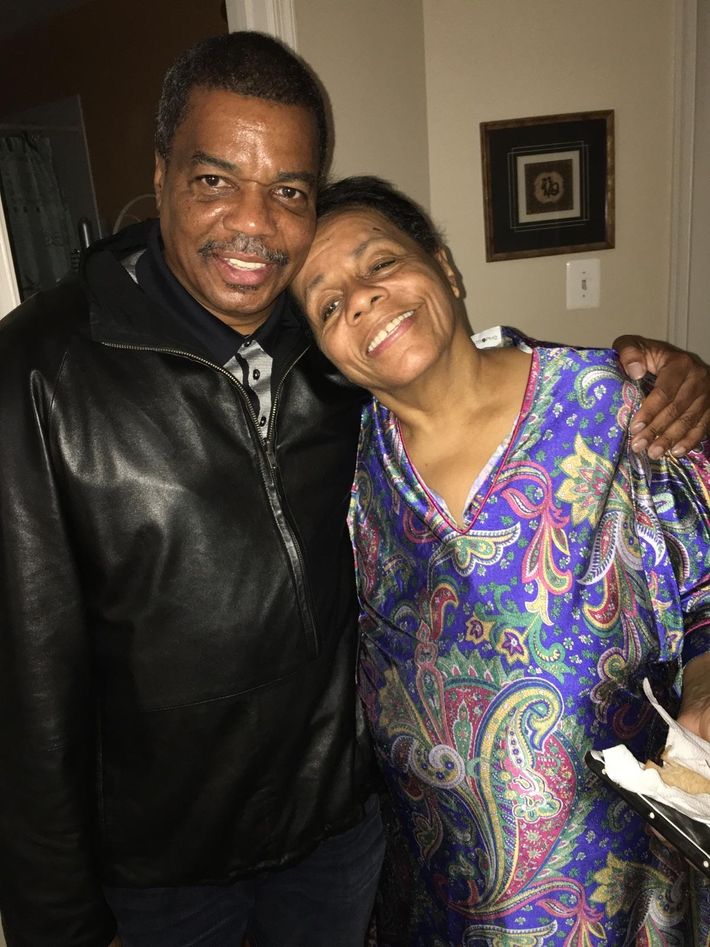

Stephanie George (photo at top of article)

When she was 26, Stephanie George was sentenced to life without parole for her role in a small drug operation. At sentencing, the judge described George’s roll as a “girlfriend” and “bag holder.” She served 17 years.

The Crime

My daughter’s father is the one that I ended up getting in trouble with. I’ve run across so many females that have gotten a life sentence either because they’re married to men that dealt drugs or men have abused them and made them stay in relationships. It’s crazy. I was sentenced on May 5, 1997. They took me to Tallahassee. That’s where I was going to do my life sentence. I was just numb. I didn’t know what to think. He did 12 years. He got out in 2008.

Going in and Getting Out

I did my first week in the SHU — the special housing unit where you’re just locked in a room. Turns out, they didn’t have any bed available out on the compound for me at that time. They come, feed you, bring you whatever you need. I thought that was where I was going to do my time. I didn’t know nothing about being out in the population on the compound. I didn’t know all of that. I probably cried the first three days.

I put in my own commutation letter at first. Probably like two months later I got a letter from Families Against Mandatory Minimums. I would always update my profile on their page. A lot of people would contact me. They asked if they could put in a commutation for me. This was in 2012. They could pull my commutation and represent me. I was so happy about it. “We’re trying to get you home by Christmas,” they’d say. I’m like, “Christmas? That’s three months from now.”

I always tried to keep it realistic. I filed so many motions that were denied. I’d say, “Stephanie, you have to think rational. If it happens, it happens.”

I found out I was getting my commutation December 19, 2013. I was at the commissary shopping. I kept hearing them calling my name to come to the office. I’m like, The office? My nerves got bad because just a few months earlier my youngest son got killed. He was 20. He got shot. So when they called me, I was shook because I have another son, and the only thing I could think was that something had happened to him as well.

My case manager handed me the phone. I was shaking so bad that I knocked everything off her desk. It was my attorney. He said, “Well, I called to tell you that just this morning at 8:45” — and it was 9:30 — “Mr. Obama signed your clemency. You’re going home for Christmas.” I got so silent. Tears were just running down my face. He said, “Stephanie, you there?” I said, “Yes, sir.”

Freedom

They wanted me to go either to a camp or they wanted to send me home with a leg monitor. But I chose to stay in prison for my four months because I didn’t want to deal with the press. I didn’t want to go to the halfway house. I didn’t know how I would react to just being thrown out. My family was upset. We went through it for six or seven months. I wanted to make preparations. I had to decide where I was going, who I was staying with. I wanted to prepare my kids. I had a daughter and a son. They were still upset. I was still upset about my baby son, me coming home and him not being there. That played a really big part about why I didn’t want to come. I hadn’t grieved about it. I didn’t want to think it was true.

My family came Wednesday night and spent the night. I told them if they wasn’t out there at eight, I’d be walking. But they were sitting out there when I came out the gate, and of course there were a lot of reporters, all across the street. I had one guy follow me all the way back home. He spent the weekend with us. I had, like, four interviews that weekend from Thursday through Sunday. It was just crazy for me. I didn’t sleep my first week home. It was too quiet.

I stayed locked up in my room. I had a TV in there. I had a radio in there. I only came out to eat, and I had no conversation. I didn’t know what to talk about. I didn’t want to go out. I stayed home for probably, like, four months.

I am very standoffish now. I used to be very friendly; I’m not anymore. I’m very cautious about who I arrive with, who I hang around, and I can count them on one hand. If they’re not my family — and that’s the immediate family — I won’t ride with them. My boyfriend’s the only person that I would go out to have a drink with.

I know that I am blessed to be home. If it wasn’t for Obama, I wouldn’t be home. I know that. I just take one day at a time. One thing is for sure: I won’t disappoint him.

Keldren Joshua

In 2006, Keldren Joshua pleaded guilty to conspiracy to distribute 500 grams of methamphetamine. He was sentenced to 15 years to life. He served ten before President Obama commuted his sentence last August.

The Crime

I was involved in DJ-ing at a young age. As time just went on, eventually I started working at Bank of America. From DJ-ing and living in Hollywood, I knew where everything was. I knew where every type of drug was. You wanted prostitutes? Okay. From being in the scene, I knew.

I had a friend who asked me if I could help someone with a methamphetamine deal. I was like, “No, this is not my cup of tea.” I did smoke ganja. But he just kept asking me. So I said, “You know what? Let me contact some friends. I might know somebody.” I contact a friend of a friend, and I eventually found some methamphetamine for him. I was like a middleman between the two people. But what we didn’t realize was that the guy who gave it to me was a confidential informant.

Driving with a suspended license was my only arrest record, and I was still on probation for that. They gave me a plea bargain. When you watch TV, you think you can say no, but the plea bargain that they gave me was a onetime offer. I either had to take this plea bargain or go to trial. And they can give you any damn number they want to give you. I looked at my lawyer and he’s like, “They’re 98.9 percent going to convict you on trial.”

Going in and Getting Out

Here’s the funny thing about the clemency: I did not apply for it. When Obama did this Clemency Project in 2014, they wanted people who were at least ten years in so they wouldn’t get flooded with every inmate in America. I saw it and knew I was only an eight-year, so I didn’t even apply for it. The following year, I get this letter that says, “You’re a perfect candidate for clemency, would you like to be involved?” Then this wonderful man, who I still talk to today, Andre Townsend, gets a hold of my stuff and he was an esquire for the federal public defender’s office. He calls me up and asks me some questions like, “Tell me about yourself.” He just put this hella-tight package together, stuff that I didn’t even remember that I did. I’m reading this thing like, “Who is this guy he’s talking about?” Then he sent it. That was it. I didn’t hear nothing back. All of a sudden you start seeing the first wave of people go, the second wave of people go, third wave. I’m counting. It’s 2016, and I’m counting as these people are leaving. I’m getting eager. I’m like, Damn, Obama’s going to be leaving soon. He’s probably got about two or three more times he can even do this. At no point in time did I actually think I was going to get it. But why shouldn’t I?

Then one day they close the whole yard and call me. I went upstairs, and my case manager is sitting there and she’s crying. I’m like, “What’s wrong? Did something happen to my mother? Did something happen to my grandmother?” She said, “No, you better have a seat. Mr. Joshua, you’re going home. The president has just released you. You’re getting your ass home.” The craziest thing was, it was on my mother’s birthday. So it was just like it was supposed to happen. That was the moment that the waterworks came down. The first thing in my mind is that I needed to call my mother. My case manager goes, “No, you have to call the United States office-of-something. Act like you don’t know.” So she called, and I said hello. “Hey, Mr. Joshua. You know that the president has just released you and you’ve made our list for the commutation. What can we do for you? Do you need a ride? Do you need help? Do you need anything? Because this is from the president, so whatever you want, it’s on us.” So I say, “Can you bring me Air Force One?” She just starts cracking up. She’s rolling. Then she says, “No, we can’t bring you Air Force One.” I say, “Oh, wait a minute, can you do me one favor? Well, since me and the president are on a first-name basis now, can you tell Barry I said, ‘Thank you very much’?

Freedom

When I first got out, I came to my house and had a whole bunch of friends here. We cooked a big breakfast, and everyone just came, and I did a toast, and that’s when I did the real cry again. I got out on a Wednesday; that Sunday, I got free time to go to church, and I called all my friends who were available and we all went to the beach to get baptized in the waters of the Pacific Ocean. To have the sand running through my feet, the California sunshine — that was the highlight. Just seeing people on the bus and the train. I went to Santa Monica, and when I first got there, all these people, all these beautiful women. Now all these women wear these aerobic pants?

I work in the most beautiful place in Los Angeles, in Santa Monica. It’s just beautiful people. I work at a shoe store that my friend owns. As soon as I was out, he was like, “Look, you got a position. You got a job. Don’t worry about it, I got you.” I got blessed with a car. All my friends have supported me. They’ve done nothing but make sure that everything’s okay. With my story, and with the support I got, I know what everybody else’s hardest part is going to be — getting that job. How do you explain on a résumé where you’ve been the last ten years? You might be able to get away with it, but if you don’t, and they do a background check, which everybody in America does now, then you’re hit.

My mom is so happy right now. She’s coming out here for Thanksgiving, my first Thanksgiving out. During Christmas, I’ll have the ankle bracelet off, so we’re going to throw a shindig. My first Christmas and my first New Year’s Eve. It will be the biggest party I can conjure up. I want to buy a turducken.

I still send my friends in prison pictures of girls. Send them magazines. Growing up, I was a big comic-book fiend. When I was in there, my uncle would send me comics. I would get them and read them and pass them to everybody else. So I’ve been sending comic books to my friends. I keep telling them, “I’m not going to forget you guys. I’d be a jackass. I know what you’re going through.”